Thursday, February 22, 2007

Lijiang

After the shocking bus ride here, Lijiang seemed quite out of place. It doesn't seem like a beautiful, rich, entirely tourist-based town with nothing but souvenir shops an fancy restaurants should exist here. Lijiang dies not share a social continuity with the coal mining villages and with their old substandard houses. Lijiang is a mirage that lets its hoards of tourists think that all is well in Northern Yunnan.

The old part of Lijiang was built in the 14th century and after withstanding a strong earthquake in the 60's, it was awarded world heritage status. All the houses have black tiled roofs and are separated by narrow cobbled footpaths. There no cars in the old section, which allows you to hear peoples voices, and the soft sounds of peoples feet on the stones or the trickle of water. A winding maze of cobbled streets and canals make up the old section. Flowing water accompanies most of the streets in town. The canal in the main plaza has a school of bright orange goldfish, and in smaller plazas there are square pools - always in a connected series of three - for washing vegetables, meat and clothes.

In the mornings, the military runs through town, shouting short, loud shouts. This way, the Naxi people who live above their ships don't forget about China.

The people here are Naxi people. They are animistic and use the only photographic writing system in use today. They build white plastered buildings with exposed red wooden pillars, and there are a few brick buildings in town. Inside, they are spacious and you can see the bottoms of the tiles being held between wooden slats. Their windows are lined with the finest latticework and carvings of scenes with birds, animals and plants. The carvings let through light in all the places between the birds' legs and delicately carved blades of grass. The doors to their shop fronts are not attached -they are removed from the building and each day and replaced each night, and if you walk through the city late at night or in the early morning, it feels like a different city without the crowds of people in the streets and in place of shop fronts, there are dark wooden walls stretching the length of the street.

The people of Lijiang like to sing. Every night groups of girls in traditional garb sing a short song from a window, and chant "Ya So, Ya So, Ya Ya So!" and another grip of people in the street or in the bar across the street will sing a song and end it with the same chant. As the night goes on, and people get drunk, the verses they sing get shorter and shorter.

The streets are lined with red lanterns and people float candles down the canals to make wishes. Red lights and the warm wooden glow coming from inside buildings and the golden light of candles in the water make a beautiful sight on Lijiang's chilly nights.

The old part of Lijiang is like an ethnic theme park. It feels more like Las Vegas or Disney Land than a village where real people live. I would not be surprised if everything is an act for tourists. Perhaps that is the role ethnic minorities play in China today. I read somewhere that most of the Naxi who used to live in their old section have been bought out and pushed along by the incoming hoards of Han migrants with more money from the cities. Yet every shopkeeper wears traditional Naxi clothes.

I expected to find the Naxi, as an ethnic minority, to be similar to the Native Americans. I expected to find something more like NM pueblos. I thought they would be herdspeiople, tribal, somehow technologically inferior to the "Chinese". In some ways, their position is similar to the Native Americans'. They are being colonized and force-fed Chinese culture. Their land is being bought up and their language is being strangled out. The Naxi are simply a people from a country that through some fluke wound up within the borders of China, and like the rest of the minorities in China, and minorities all over the world, they are undergoing cultural genocide. It will not be surprising when the next generation does not teach their kids to speak Naxi, and if a few generations later, they simply call themselves Han. Being an ethnic minority in China is a mighty struggle. The central government is relocating people from the coast and other parts of China to the Western regions, creating minorities out of the cultures that live there, forcing them with the choice between assimilation and inferiority.

We met one young girl here who says she would rather speak Chinese or English than Naxi. It is a shame that an economic and bureaucratic Chinese dominance can make a language and a people irrelevant. They call Lijiang county a Naxi Autonomous Region, but all business must be conducted and written in "Chinese. Perhaps fewer Han would move here if the Naxi still held linguistic authority - if all the signs, labels, receipts and banks only operated in Naxi.

The new city of Lijiang is a typical Chinese city. The traffic, the market, the architecture, the chain stores, all of it is almost indistinguishable from other cities in China. Except, perhaps, for the vacant lots of rubble overgrown with weeds and weed!

Road to Lijiang

After leaving Pan Zhi Hua for Lijiang, one of the first things you see are mountain sides of coal that fall directly into the river. there are factories with smokestacks and coal elevators, a cable car with only containers for coal that is carried from the mountains to the riverside industry. Three nuclear power plants also help to warm the river just outside of town.

As the city traffic tapers off, the roads become full of big trucks overloaded with coal. The small towns along the way have traffic jams of the big blue dump trucks of coal. In small yards along the way, black dogs are chained to guard black ground where people with black hands and faces pound powdered coal into perforated round bricks for cooking. The sky is a smoky blue, even when there is nothing but terraced hills of rice in sight. These lonely country roads are arteries of coal being carried out past poor peasants in massive blue trucks that don't stop in the villages.

We passed through a valley full of beautiful rice paddies beginning to change color with the seasons. Terraces with rounded edges climbed up the steepest hills. Farmers worked in some, putting the rice into cone-shaped bundles to dry. Goats, water buffalo, horses and cows all shared the road and grazed along the unfenced fields. Everything up to the cliffs was terraced. Even small islands in the river had been completely conquered by rice. Where there was no rice, corn was grown on the terraces.

Past some of the most b beautiful scenery I've ever seen, our bus took us along a road carved into a cliff above the river. Across the river, we could see mine after mine with an alluvial pile of tailings cascading down into the river. Some were just like a doorway into the mountain, and others were entire hillsides with switchbacks for trucks and no trees. Where there was room, people were living on the tailings, in small hand built houses with black yards.

It is no wonder that China has "cancer villages" where 30 -40% of the people have cancer. I wonder if any fish can survive in those brown waters below the mines.

Chengdu

After leaving Xi'an for Chengdu, our train had some high mountains to steer around and tunnel through. The day was just getting light as we entered Sichuan province, and every time the valley widened enough, there was a nuclear power plant. One after another, like tumors on the river.

In the train, we made friends with a company of petroleum engineers heading to Panzihua for a meeting. They offered us beers and we talked and sat in their carriage. A bag of meat was passed around, there was no choice but to take some of what was offered. It was spicy pig stomach. As the night progressed, we came and went and a mound of trash grew on the floor in their sleeper compartment. With my feet buried in it, my exposed toes were kept warm by something behind a plastic bag. The only lady in the group was a higher-up in the company, and she told me not to worry "it's only trash, and rabbit heads". Later on, a cleaner came to take the trash and took a dozen warm greasy bags filled with rabbit heads in red sauce. With all the trash removed, my toes and the floor were covered in a thick layer of grease. Everyone was drunk, and we went to our own beds.

Chengdu is the capital of Sichuan province. Sichuan province was created sometime after the Cultural Revolution out of Ganzi, part of the Tibetan autonomous zone and minus Chongqing. Chongqing is one of those Chinese cities with tens of millions of people that almost never makes headlines in the West. Now nearly the largest city in the World, Chongqing was made a separate province to prevent Sichuan from gaining too much influence over Beijing.

Chengdu is a medium sized city of four million built up around some of China's most fertile land and on the border between the Chinese and the Tibetan worlds. In central Sichuan, the climate changes and becomes almost subtropical, and despite the drought, it is incredibly green and humid. As we have been travelling through China and reading headlines of this year being the worst drought in 50 years, we constantly tell ourselves that the drought must be somewhere else, somewhere our train has not passed through. Footage on TV shows parts of Sichuan where the water table has fallen and water, mostly to drink, is being shipped in in tanks in the backs of pick up trucks. It must not take a dust bowl to destroy crops.

Travelers arrive in the train station in the far North of the city, where all of the buildings are new and already falling apart communist style apartment blocks. The avenues are lined with trees, wide and full of traffic. Canals penetrate every part of the city and one of the rivers flows in a brick lined channel five meters below the city. Under a small bridge where clear water flowed into a canal, it created a window in the otherwise black stinky water where the rocks and plants on the bottom could be seen.

Arriving in chengdu, we were greeted at the station by a guy named Edward who was holding a poster advertising his hostel and who spoke excellent English. He and some of his family run a hostel here, and it is the nicest one we've stayed at in China. The hostel has achieved a hard to describe atmosphere that makes you feel at home. Perhaps it is an atmosphere created by the hostel or perhaps it is Chengdu that causes most of the travelers here to sit around the hostel all day and to remain in Chengdu longer than expected. The hostel, unlike most in China had self-serve laundry, an indoor courtyard and a small fish pond. Mostly European travelers lounged around, ate late breakfasts and played games in the halls and in the courtyard.

Chengdu is a city of tea houses. In many areas, tea seems to be their most common cause for business. There are not particularly many attractions in Chengdu, so tea becomes part of any visitor's routine. Downtown, the buildings are newer with glass-walled high rises and banks with carved gold plated doors fit for castles. Downtown is packed with people and rickshaws, constantly ringing bells at people straying from the overflowing side walks and cars that slowly push their way through cross traffic and defy the structured organization one might imagine is common to all busy roads. Drivers here do not honk as much as they did in Xi'an and far less than drivers near the coast. The rickshaws here are not like the ones attached to motorcycles in Xi'an; here, they are all powered by bicycle. The drivers are only seldom young and strong-looking. Usually, they are older, well-worn and tired-looking people.

"All business is done in tea houses", Edward told us. The tea houses are nice, with big comfortable chairs and prices that must only invite Chengdu's niveau riche. The presence of so many tea houses and the culture that goes along with drinking tea (even if it is mostly business men who go to many of the tea houses) has given Chengdu a noticeably slower pace than many other of China's large cities. There is a clear split in the service industry between places that cater to the well-to-do and those for the common people. Prices are hard to describe here as they vary widely.Today, a Chinese friend and I ate a lunch of noodles at the market for six yuan, this evening, Aja and I had a small pizza and two drinks for 75.

I went to the market with my friend Nick, and we shopped around for several hours for some saucers and plastic cups. It is not that there were any shortage of such goods at the market, but Nick wanted to be sure to get the very best price. Nick wanted the saucers to drink a special kind of Chinese liquor from in traditional style. There were no very shallow cups of the sort at the market, and he settled on some bamboo saucers made to go under tea cups. After asking in a half a dozen stalls about the price of cups and hemming and hawing about weather he would pay 3 or 4 yuan for a cup, he finally settled on one of the first shops we had visited, renegotiated a price, which he was not completely happy with. "I would have liked to have paid two" he told me.

The market was a haphazard arrangements of hundreds of stalls selling everything that can be mass produced. Heaps shoes with ripped-off name brands that looked just like their corporate twins were being sold by young guys eager to make a sale, but who only hesitantly admitted that the brands were fake. Some shops only sold chop sticks, some sold pots and others sold lights. Nothing had a set price, so every sale required a drawn out discussion where the customer would degrade whatever he wanted and ask a price far below what he was willing to pay. The shopkeepers worked hard to pull people into their space to look at whatever they had that a dozen other stalls in the market undoubtedly also had. The market is like a loud beehive of people buzzing around between different stations.

The market occupied a small neighborhood. Parts of it were indoors or under a large tin roof, and parts of it spilled out into the street. Nick took me to lunch in a restaurant that, although there was no wall between it and the street, it was almost invisible amongst the clutter that was the market. We ate spicy Sichuan style noodle soup and Nick was a little surprised that a foreigner was able to tolerate the spiciness of it.

Nick helped us get discount tickets to the Sichuan opera, which far outdid the Tang Dynasty Opera in Xi'an, and afterwards invited us to his house.

The opera was a fantastic performance of acrobats, magicians and people who could do spectacular things. One young girl, perhaps 14 years old balanced a large clay pot on her feet and spun it, kicked it up in the air and rolled it around in every direction. Then she did the same with a table. Another act involved an argument between a man and his wife, and she made him blow out a candle placed on his head, and he did. He also was made to crawl under a low bench with a candle balanced on his head and then get up again. The feature act was one called Spitting Fire Changing Face. These actors learn their act from their parents and the trick stays a family secret. They have masks on, and in a split second, they will wave their hand and have a different mask on or no mask at all. Of course, they also spit fire. One of them came into the audience and shook Aja's hand, and just as their hands met, his face changed right in front of us, and surprised us both.

Stefan

I wanted antibiotics for a mild stomach problem, and in the hospital, where the nurses couldn't speak to us, they called out for anyone in the waiting room who could help translate. A young guy volunteered, and after he confused some German words for English, it came out that he had studied music in Vienna and spoke good German. He helped us buy some antibiotics and Qinghao, a Chinese herb that is said to cure and prevent Malaria (and paid for them), and then took us to a museum where he paid for our tickets. He spent his whole afternoon with us. We were the only visitors at the Sichuan University's ethnography museum and Stephan helped explain some of the old artifacts and told us stories about the area.

We got Stephan's phone number and called him later to come hang out with us and Nick. At a portable shish-kebab stand we bought meat and vegetables grilled over coal and sprinkled with MSG to bring to Nick's house. Next to the kebab stand, a business in a large wooden box built onto the sidewalk sold us a bottle of hard liquor to drink from saucers.

Nick lived on the top floor of a typical communist style building tucked away on a small graffiti filled alley off of a 6 lane downtown road with his grandma.The walls in the stairwell leading up to Nick's apartment were covered in papers and stickers. Most of them advertised locksmiths and other domestic services. His grandma was asleep, but Nick told us that she had washed the saucers he bought at the market several times. There was little in the house. A light bulb hung from the high ceiling on a long wire. Nick had begun a mural of faces melting into each other in a swirl of black lines on the wall, but his father told him he had to stop because he might want to sell the apartment soon. We sat around a low table made of a board sitting on two boxes and learned how to play Majong.

In the Southwest of the city there was a Tibetan market. Not much seemed to be left of it. Since our map had been made, it had become an upscale part of town with almost western shopfronts behind large panes of glass. A few of them sold Tibetan clothing, carvings and souvenirs. Dumplings for half a Yuan sold at one restaurant from which steam billowed up onto the sidewalk through the stacks of bamboo dumpling trays. Near the Tibetan market was a section of the city centered around some pay-to-enter gardens that had been restored in traditional Tang dynasty style. The wooden eaves had all been painted red and green and red paper lanterns hung down in the narrow streets between high gray stone walls. Tour buses full of tourists filled the cobbled corridors and photographers with portable printing stations waited for groups of people to buy their photos in front of the picturesque walls. Nothing but tacky tourist shops and every sort of restaurant lined these popular streets.

At the center of Chengdu is a grand stone statue of Mao, and from him run the four major directional streets found in most Chinese cities: Renmin zhonglu, donglu, nanlu... and further out, the city is encompassed by a circular highway. In the Southeast, there are a row of electronic shops, three universities, and a few bookshops with English language books and a delicious Tex-Mex restaurant. The sweet smells and tastes of home was satisfying in the way no other food is. They played country music softly and American students and visitors took most of the seats every night. To walk across the city from the Tex-Mex restaurant back to our hostel took about 4 hours. no bus because of construction..

Renmin park is the highlight of the city. In the Northwest, it is a big, free park with ponds and a trickle of a stream running through it. Winding paths lead through a plaza where kids roller blade and past groups of older folks singing karaoke and others dancing folk dances and dances with flowing red scarves to music playing on blown out speakers. It truly is a people's park. Under overgrown lattice roofs where no one danced, people crowded around old men playing Chinese chess. In some corners of the park, old men in Mao-hats played sad songs on their one-string violins, sometimes alone, sometimes in groups. A couple practiced Tai-Chi in a garden. A tea house in the park served a great variety of green teas in clear glasses with a big thermos of hot water. Men with tiny instruments like chimney sweeps that they vibrated with a tuning fork offered to clean people's ears as they drank their tea.

The park's walls kept the noise of cars and horns out and offered a momentary escape from the city. Barriers of trees and bamboo and wandering paths made each part of the park seem self-contained, invisible from every other part.

Emei Shan

Emei Shan is the most beautiful place in China. It is a little island of paradise still untouched by the grime of the cities. It was a sacred Buddhist mountain, stripped of its monks by Mao, and now it is a tourist attraction preparing for the Olympics (a new golden multi-faced Buddha statue built on top). Monks have returned to the monasteries with their cell phones and incense. Every morning just after 5:00, they wake up and chant and ring their bells and gongs and start their day.

Emei Shan is the most beautiful place in China. It is a little island of paradise still untouched by the grime of the cities. It was a sacred Buddhist mountain, stripped of its monks by Mao, and now it is a tourist attraction preparing for the Olympics (a new golden multi-faced Buddha statue built on top). Monks have returned to the monasteries with their cell phones and incense. Every morning just after 5:00, they wake up and chant and ring their bells and gongs and start their day.

Monkeys live on Emei Shan. They roam around in groups, and some sit by the trail waiting for snacks from hikers, or whatever they can easily steal from unguarded backpacks and pockets. They are friendly, but wary of people. They will show their sharp teeth if you get too close, they will crouch down if they feel threatened, and they growl as they follow you, waiting for an opportunity to sneak a hand into your bag. They are well groomed, but with red patchy skin on their faces and nervous expressions. They look like little wild people.

There is a good reason the monkeys are so wary of people. The people on Emei Shan seemed dead-frightened of the little macaques. A group of ladies walking in front of us told us we needed to arm ourselves with stones to protect ourselves from the monkeys. They held rocks larger than their fists. Some monkeys were in the path and these ladies told us to go ahead of them to take pictures and then proceeded to aggressively scare them off, throwing their rocks and waving sticks. An old man we passed stood on a ledge with a slingshot, shooting small stones at monkeys still quite far from him, and certainly not posing any risk to his bags. On a stone step was a tiny pool of blood.

The monkeys live in steep valleys where every cliff is dripping with water and the rivers are crystal clear. Every morning, the cool air turns the clouds that hang on to the mountainside into a misty rain, not quite strong enough to put out incense or candles burning in the courtyard. The water in the streams is crystal clear, and the trees grow moss on their black trunks. The whole mountain is covered in life. There are hundreds of colorful butterflies, dragonflies and we even saw a frog swimming through a crystal clear stream flowing between tall green cliffs.

From bottom to top, the pathways are paved with stone steps. It is an amazing feat of the Chinese to build stairs up all their sacred mountains. Today, some stairs are being rebuilt, not by monks, as I had imagined, but by workers who carry the stones, two or three at a time tied to the backs of mules. Climbing up and down the stone stairs with such heavy loads, the mules were exhausted, walking with slow heavy steps. As we ate lunch at a mist covered pass, a train of mules lumbered past us coming out of a blanket of fog and quickly disappearing into the whiteness of the dark forest.

After falling into disrepair during the cultural revolution, some of the old temples are being renovated, but many are still falling apart, suffering from the long absence of monks, who have only recently started returning. At a monastery with a tin roof and multiple slowly progressing restoration projects, there was a small shop selling food, water and walking sticks, we bought some more water and beef jerkey. It was only a few hour's walk from the top and only a few hours before dark. People at an inn behind the monastery warned us not to proceed and told us to stay with them. The next passers by also warned us that we would not make it to the top before dark. As the sun got low, we passed by a hut selling fruits and asked if we could stay there. No, but we bought some bananas. Just after it got too dark to walk in the woods, we reached a cliff from which we could see white clouds moving below us. Then, after walking for ten hours, we reached a parking lot. It was 8pm and we went into a fancy looking hotel and asked about their prices. 430yuan, they told us. We had paid 60 the night before in a monastery. "Sixty" we said, and they agreed almost immediately. We got a room with a sign on the door that said "Conference Room" and went straight to sleep.

On Emei Shan, you almost forget that you are in China. It seems like all the traffic, pollution, power plants and stinky cities must be on a different planet, far, far away. On Emei Shan, there is no drought and no environmental crisis. Emei Shan is like an escape from the unbearable problems existing in the rest of China, or a place you can safely convince yourself that they don't exist.

Monday, October 23, 2006

Saturday, October 21, 2006

Two saxophones and an oboe played slow, sad songs in the park. The musicians were all retired and one man sitting near me of that same generation knew all the songs and sang the best parts of them. His scruffy dog got attention from all the kids who passed by. He asked me where I was from, and another guy joined us.

Just a little older than I, with short hair in the back with a long tuft in the front sticking straight out, came over and asked me the same question. He sat next to me, facing away, and without making eye contact he began to speak to me in impeccible English. He spoke quickly, almost nervously, and began to tell me a story.

His story began with how hard it is for people to find work in Xi'an. "There are no factories anywhere near the city center so there is very little opportunity. Wages are low, and government corruption is high. Without the welfare system, China would fall apart. Even I am on unemployment, these musicians are retired, that's why they can play here." Pointing to the old women in their simple, colorful clothes walking in close groups, he said "see them -- all these women are from the countryside."

In China, it's very hard to get a job. To get a good job, you have to have a masters degree, but even then, it's hard.

He went on to talk about Education in China. "Education in China is expensive. Parents have to pay for their schools, even primary school. Rich kids get spoiled - because of the One-Child policy; poor kids get left behind. In the countryside, it is particularly bad. You see, none of the kids who get an education will go back to the countryside to work. The wages are too low. Too low to live off of. So what winds up happening is older students teach thier younger piers instead of trained teachers. For the kids, all that matters are exams. They are always multiple choice. For English, kids may be able to choose the right answer, recognize nouns or verbs, but won't have any idea how to understand the language.

"When I pass my certification exams, I want to teach English. Or maybe I want to be the headmaster at a private school." All the headmaster does is make sure students attend class, and he will call the parents, or if the kids don't go out for morning exercises, he will make them go out. But, even headmasters do not earn good money. Now, what's happening is college students are offering tutoring in English for younger students.

"The young people here, they worship Western culture."

"Our economy is bad now. Too much political corruption. It used to be that politicians earned the same as the common people, and that led to corruption. Now, they will buy up land and sell contracts to develop it, then sell it for more money. They will buy up large pieces of land very, very cheap. Now they all have big fancy houses, their kids get the best education.

When someone buys a house in China, the land still belongs to the government. Your house will get a 70 year lease, after which, it is returned to the government. So if you buy a house on land leased sixty years ago, you don't know what wil happen to it after 10 years. The lease will expire, and you may not have any legal claim to it.

"In Mao's time, things were better. People had less, but everyone was satisfied. Now," pointing to the ladies from the countryside, "even the poor country people wear nicer clothes than the politicians then. Now, people have cell phones and they need things. In China, if I loan you money, or if the bank loans you money, you never return it. It just disappears."

Today, a teacher at a public school in Xi'an earns about 2000 Yuan a month. 20 years ago, it was less, maybe 100, but everybody earned 100 and people had enough. Today, our future is black. NObody knows what will happpen in china in the future.

Now, our president is better than the last one, but he cannot create change. He cannot fulfill his promises. Nobody knows what is going to happen to China. I don't know what we need to do.

"China is a peaceful country. We never attack other countries. Only small countries attack us. Vietnam, England, Portugal, Japan. That's why we need a big army: to defend against small countries. How does Portugal defeat China? Because we think Portugal is a big country, we listened and when they said give us money, we gave them silk adn backed down. That's why China is poor now. Small countries have always been taking from us. We're not like America, who is just invading small countrys, just attacking Iraq for oil."

Xi'an

-----

Xi'an is the center of ancient China, the beginning of the silk road, one of the world's most polluted cities, a busy modern city with lots of banks, brothels and heavy traffic. Xian marks the edge of the muslim world and the center of the Middle Kingdom. Here, there are more int'l brand name shops and more beggares and homeless than in the cities we've seen East of here.

Xi'an is a world-class city, older than Rome, doing all it can to prepare for the expected wave of tourists coming with the 2008 Olympics. Here, too, every shop is overstaffed adn nobody trusts you to be able to choose what you like in a shop without help.

Tonight, we went into a crowded restaurant, but couldn't read the menu. Aja wrote chicken and vegetables and 5o Yuan ($6) in Japanese and we were brought a feast! The best food we've had yet. The Chinese food you find in China doesn't tend to resemble too closely the Chinese food served in the West. Everything is deep fried to death, and we are warned not to eat anything fresh because the water it's washed in could be too toxic for our soft stomachs. Yet as we move away from the sea, the food improves. In China, the mountain food is much better.

--------------------------------------------------------

A short bus ride from the city are the tombs of the first Qin emperror, who first united Central China by conquering the neighboring countries. He began construction of the Great Wall, and employed an army of 700,000 people to build an army of clay men to guard him in an underground city and palace after his death. This grand project was then buried under five meters of earth. Today, he is the hero who united China, but he was so unpopular that soon after he died, his tomb's army was sacked, burned and forgotten.

Under massive roofs, the Qin army has been unearthed and reconstructed. Seeing these people captured in clay, made with such care and skill, and each with his own personality showing through their clay skin, it is living people you see. Most of these men were larger than contemporary Chinese people and myself. (Perhaps Qin dynasty people had a better diet?) They all had different expressions, although no one's face or movements were exaggerated at all. They were all calm, not posing, but silently waiting, standing guard.

Standing in their presence, I felt as if I had entered a very holy place. This was the first shrine I've been to where I truly felt that a soul was enshrined, embodied in the space and in each statue. When the tomb was being excavated, one body was found in perfect condition, with peaches still fresh and words written on Bamboo leaves and preserved in water. When these things were discovered and exposed to air, the peaches turned to water before they could be photographed, the body dried up, and the calligraphy on the Bamboo leaves disappeared as the leaves turned black and curled up when removed from the water. The archaeologists mush have broken a powerful spell when they entered with their cameras and fresh air.

The relics of the underground palace are safe, for now. We don't yet know how to build a building big enough to cover that large an area nor do we have the technology to pump out the aquifer that the city lies under.

The tombs with the warriors were discovered in the 70's when some farmers digging a well found a statue. They were frightened. They thought they had unearthed a god and made it angry. But they quickly became folk heroes adn received state visits and got in newspapers as archaeologists discovered what a treasure they had found. They were not the first to dig up a statue, though. One of them told of his grandpa who dug one up in 1911 while digging a well. This statue stood until the well went dry. The farmers thought the warrior had drunken all the water and was smashed to bits. This has happened many times over history, but it was not until globalization and the 70's when finding a buried statue triggered a national wave of excitement.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Shaolin Temple August 24

Shaolin sits nestled between steep mountains in a place the Taoists consider the center of the world. There are thousands of Kung Fu students wearing differen uniforms representing the many local schools. They practice their moves in the temple ground's many courtyards and open spaces. The mountains come and go behind clouds of mist. Barely a trickle flows through the canalized river full of plants in front of Shaolin Temple and the ground above it is dry and cracked. The monks, or perhaps it is the other people who live here -- people who run hotels or old ladies who collect plastic bottles--have patches of corn, chilies and other crops growin on the hills, barely kept separate from the wild vegetation.

In the morning and evening, the traffic shifts from being that of tourists to the rusty, clunky tractor-wagons that the farmers and workers drive. On hills, even motorcycles turn off their engines and cruise slowly with squeaky brakes and rarely with only a single passenger. When we arrived in Dengfeng, shaolin's supporting city, we were immediately harangued by a crowd of men waving Shaolin flyers and who shout Hello at any foreigner. One who spoke only the English required to give a repetitive speech about how he would give us a ride and that Shaolin is 17km from Dengfeng and that there were no busses and no places to stay inside Shaolin so we should go to a hotel he knows attached himself to us until we agreed to take his ride. A thoroughly obnoxious man whose lie about there being no busses we believed after asking a bus station worker who carelessly answered our questions with no, no, no. Or driver didn't want to take us to the temple. He insisted it was too late in the day to see the temple and that if we bought tickets, we would not have time and we would not find a place to stay, and we really should go with him to a hotel he knows. If he hadn't been so annoying, we may have taken his advice.

We didn't worry about finding a place to stay. Wearing our large backpacks, we stood out as people who hadn't yet found a hotel and we became the target of, first one, then two, three, four, and finally five ladies waving hotel business cards at us and refusing to go away. Every time they felt they had lost our attention, they shouted a crisp "hello" at us. We wanted them to leave, we wanted to look around and go to them when we wanted their services. I tried to write to them using the Japanese Kanji I know, which got them excited and they began writing to me in Chinese instead of shouting. Aja ran away to some Italian guys to ask them where they were staying so we could rid ourselves of the pack of ladies who were firmly latched on to us. They gave us the business card of the hotel, and when we showed it to the ladies to show that we had made up our minds and didn't need them, they reached into their purses and pulled out the same business card. We ate an ice cream, and set off.

To get to the hotel, we had to buy tickets and go inside the temple grounds. The most aggressive of ladies following us was stopped at the ticket gate. She tried to run around it, but was stopped again. The Italians and we went down a slope and waited for a van to pick us up. Just before we got in, not one, but two of the haggling ladies had evaded security and were running towards us. They got to the van, but were shoed away by the driver because there was no room. They didn't stop them. They pushed the Italians over and one sat on the other's lap. We laughed and laughed from the back seat. At this point, they served no purpose, but hoped desperately to receive a commission.

Our hotel is in a tall cement building painted to look like a grey brick building. The women working here are quite curious and nosy about everything we do. One young girl who works here wants to be our friend, and tries to teach us Chinese. Other times, she just sits close and smiles.

Shaolin temple is a large walled complex with tall pagodas that are freshly painted with bright colors under the eaves. There are big golden statues of Buddahs and past Kung Fu masters with wild expressions carved on their faces. There is a courtyard full of stelae, and one ofthem, under an ancient Gingko treeis from Courtney's master in Albuquerque.

Next to the temple is an area with older, unrestored buildings, dirt roads and piles of rubble. In this area, we went in a brick building with a plastic roof and dirt floor that smelled like earth worms to watch a performance. The performers pushed their bodies to do almost superhuman things. One person tied himself in a knot and twisted around like a rubber toy. Another became a monkey and climbed to the top of a pole he was carrying. They sped across the stage, movingflimsy and rattling weapons in all directions as fast as lightning. A drunken master flailed across the stage with a controlled sword.

We caught a few stories behind some of the buildings by placing ourselves with a passing tour group of Spaniards and Aja translated for me:

The Pagoda got its name because Damo refused to take any students, saying he would teach when it snows red. One determined monk decided one snowy day to chop off h is arm and ask for teaching. To remember this act of self-sacrifice, this shrine was built.

I assume the one armed monk became Damo's disciple, but the guide didn't mention it.

Trying to escape from another commission-seeking salesman of sorts, who attached himself to us at our hotel and followed us saying "hello, hello" and pointing to places we didn't want to go, we slipped into the first temple we passed. We had to show our tickets, so he couldn't follow us.

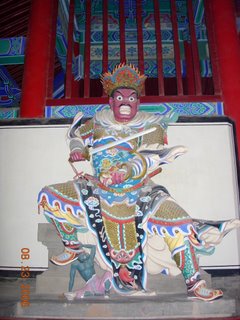

In this temple, we were first greeted by a huge Buddha, and then went to a winding system of dimly lit corridors filled with the most interesting statues. They were people from all over the world made out of shiny glazed clay and in the dim light, they almost came alive. They were all doing different things. Some were meditating, some doing Kung Fu. They had thoughtful, sleepy, angry and joyful expressions. One frightened looking statue stood with one foot on a tiger.

Pagoda forest in Shaolin

Tai Shan

.

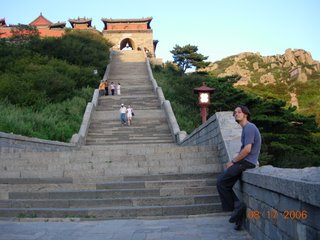

Tai Shan is a sacred Taoist mountain and the most climbed mountain on earth. It has been climbed by many past emperrors, and when Mao climbed it and watched the sun rise, he exclaimed "the East is red". On top is a huge temple complex, a range of hotels, and a host of vendors selling the same things as the vendors in the city. A cool wind blows, and the air is finally clear enough to see that the sky is blue above. From here, through a haze, the city of Tai An is visible and even it has a pair of cooling towers. The horizon in every direction, just below the top of the mountain is defined by a dark brown line of smog. It covers everything, not only the city, but the mountains on the other side of the mountain as far as you can see. A clear day below the smog never has a clear blue sky, it is always like looking up with sunglasses on.

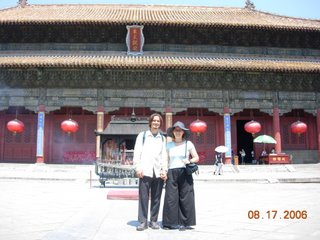

The staircase up Tai Shan is an impressive raised stone staircase almost the entire way up. The path is on such a grand scale, that it would certainly make the Great Wall slightly less impressive. The way is lined with gates, temples and vendors. The temples have stone or brick walls with dark red plastered walls and colorfully painted tile roofs with clay animals walking out on the upturned corners. Inside are the statues of the gods of Tai Shan, and people make prayers by lighting incense sticks as thick as my arm and locking locks to the incense altar that slowly get covered in ash.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Our last night in Qingdao, we moved to another guest house in another part of town. Moving across town was like moving to another country. We moved down the coast near where the beer festival was, near a yachting club, and into a hostel run by Koreans. This part of town, a 15 minute taxi ride from the inner city had wide sidewalks, new buildings and freshly trimmed hedges. This was the clean side of town, the rich section, completely separate from where we arrived on our ship. Here, the money was crisp and the rows of restaurants with eels, crabs, clams, snails fish living in shallow pools in styrofoam trays on the sidewalks to keep them fresh and attract customers were not present. Here, the streets didn't stink of fish or sewage. Here, we got our first glimpse of China, the superpower. It finally felt like we had arrived in the country we had read about on the news with its exploding economy and niveau riche.

With Song, Miree and two other Koreans we had just met at the guest house, a brother and sister traveling together, we went to the Tsingtao Beer Festival. A huge festival full of games and beer tents reminiscent of Germany. The beer hall we drank in had a big stage built in the center where people sang Chinese songs to Schlager music.

Aja and her new Korean friend, Eun Young, tried to get Chinese people to play Janken (rock paper scissors -- hugely popular in Japan) with them. They succeeded with a table of middle-aged folks who handed us both beers and chanted for us to chug them. Aja drank two more than she wanted to. We went outside and played circus games and watched fireworks. Then we found a taxi that would take one more passenger than he ought and went out for massages.

Near our hostel was a small massage business that gave super cheap massages (25 yuan~$3). All five of us were put to sleep. They just let us sleep for a long time, and finally we woke each other up, paid and went to bed again. We all ate Kimchee for breakfast and perhaps because of our massages, no one was hung over.

Our train left early, too early for us to have eaten breakfast, but when it was served, I couldn't resist. A slow driving, honking taxi brought us back to the poor part of town, back to the station and we ran through railway security where our bags were x-rayed and found our train. We were the last people to get on the train, and had to run through a thick white cloud of diesel smoke to get on our train.

Our train was pulled out of the station only a moment after we had gotten on. Through the city, we passed gangs of railroad workers without shirts wearing straw hats, sitting around with food or cards or just sleeping wherever there was shade. Before we were out of the city, we passed by dozens of small factories before we went by some truly large factories. Some were at least a mile long, with mountains of coal, criss-crossed elevators for grain, rocks, coal, I can't guess what. Here, we saw more skinny railway workers, mostly not working, families walking along the tracks that led to their factories. It didn't look like scenes of this era; it looked more like old photos of America in the '20s.

Once we were fully out of the city, the countryside was packed with crops. Vast fields of corn stretched out to the horizon and forests of young trees planted in neat rows covered the hills. Small farming villages still gave a slight reminder that this used to be a German colony, but they didn't look like German villages. Rather, a single German house reproduced thousands of times in on of Qingdao's colossal factories. Every house was built the same, but all are in different states of disintegration. It seems like many have been bulldozed, leaving others standing by gardens of rubble.

Further along, towns and cities dotted the landscape underneath a warm brown layer of smog. In nearly every city before Jinan, was at least one prominent cooling tower growing right out of the houses. There was no space between power plants and apartments.

At each stop, our train became more crowded. We moved to our assigned seats next to a nice looking young family. In the seats in front of us, an older man with messy Mao-like hair and blue jeans laid across two seats. When the young lady with a large suitcase and curly hair,whose seat his feet were on got on the train, she scolded him and demanded that he move. With a voice that changed pitch with each word, he flatly refused to move. The young lady raised hell and people bent their necks around their seats, watched curiously and smiled. Eventually, some of the blue-coated train workers came to help, but even they were unable to persuade the balding old man to sit up. Some time later, they came to an agreement that involved another man sitting in the lady's seat, while she stood until a seat opened up at the next stop.

Salesmen walked through the trains. One made the whole car laugh and used us for some of his jokes. Another convinced us to buy some nearly indestructible socks that he beat with a steel brush, pulled a nail through and showed it without any signs of wear.

Arriving in Tai An, we were met at the station by a barrage of people selling maps, offering taxis and hotels and a Tourist Information office that offered absolutely no help. We set off with only our Lonely Planet intent on going to a hotel at the other end of town. Quickly, we got a better offer from a lady boasting a brochure with pictures of hotel rooms for the Long Tan hotel near the station. The picture of the hotel on our key card was of a completely different building and caused us to walk in circles looking for it later that night.

Tai An is a big city with long city blocks. The big streets have separate lanes for the slower moving bicycle, moped and red motorbike rickshaws. Whole families ride by balancing on a single moped. The streets are noisy and stinky. Horns honk constantly as if the city were filled with an everlasting parade. Traffic doesn't stop at red lights and crosswalks are chaotic. Neither pedestrians nor cars have the right of way and are constantly competing for an opportunity to push through the ever-present swarm of bicycles and motor bikes. The green men on crosswalk s move to draw attention, but they are actively ignored.

Friday, September 22, 2006

We went to the temple of the goddess of heaven, who is also the goddess of the sea. It was a colorfully painted temple with swirly, distinctly Chinese paintings of scenes from old tales of deities, and intricate patterns. Tour groups crowded the temple and were each being led by a fast-talking tour guide holding a flag and talking through a megaphone. Tour groups were coming in, forming so quickly that there was hardly a moment of silence between when one megaphone moved on and the next came to take its place. The groups crowded around the important places, took their pictures and were hurried along to the next site.

Each hall of the temple was uniquely decorated. In the entrance, was a wooden peacock carved out of the stump and roots of a fallen tree, the fused and tangled roots polished into feathers. One room had hundreds of statues painted brightly, guarding a goddess with many arms. Another room was full of monks in robes sitting at tables with magical items, waiting to tell people their fortunes. Another hall had a Buddha in a glass box filled to his neck in worn out paper money of little value, each with a picture of Mao; a display of China's two important philosophies.

On the shore by a busy street and below a wide sidewalk was an old shipwrecked fishing boat with half its hull worn away by time. Old men walked along the rocks looking for crabs to eat or put sell. Where the shipwreck sat was surely in view of where the 2008 Olympic sailing games will be held.

In the old German section of town are large buildings with red tiled roofs and Roman style pillars in the entranceways. Inside, you can see that the wooden stairs are no longer level, and just as you wonder if it is abandoned, a well dressed girl with high heels and a shiny purse walks out.

We came across a park full of old men playing cards and Chinese Chess. Each game was surrounded by a wall of passers by who all seemed to take sides and give advice freely. With each move, the old men would slam their piece on the board, and for a decisive move, they would put their pieces down with even more force to make an even louder noise. The advice coming from the crowd made it a team sport and made sure it would be a good game. Just before each round ended, when it became obvious who had won, the crowd smiled and chuckled. All around, people seem to be enjoying themselves. China seems to have a slow pace and support ample leisure time.

Thursday, September 14, 2006

中国 China

We made it safely to China on the slow boat from Incheon! We barely made it to the ferry terminal on time. From the train station, we eidn't know where to go, my front tire was flat, ans people we asked said it was very far. We left our bikes unloked on a busy street and flagged a taxi, hoping we would not return to our bicycles.

We made it safely to China on the slow boat from Incheon! We barely made it to the ferry terminal on time. From the train station, we eidn't know where to go, my front tire was flat, ans people we asked said it was very far. We left our bikes unloked on a busy street and flagged a taxi, hoping we would not return to our bicycles.At the terminal, there was nowhere to exchange money and Korea suprised us with its price tag, so we had just less than enough cash to buy our tickets. I had to use my credit card, and am not sure if I exhausted the credit I had overpaid my balance with before I left Japan.

Our boat to China was even larger than the ship we took from Japan! From the enterance, there were two escalators leading up to the three stories of passenger ship, perhaps 40 feet above the water.

In the harbor, little silver fish swam along the edge of the boat and seagulls flew in big circles hoping to catch cheetohs from young passengers. The ship's huge engines thundered and sent a steady black cloud downwind.

People waited on deck, excited, taking pictures, feeding the birds, leaning over the rails and making new friends. One boy with a Japanese-style blowdried and died hair wearing first a grey and then a pink version of the same shirt that said something in Engrish about alcohol, cigarettes and party was taking pictures of himself for most of the trip. We watched him standing on deck with his cell phone, striking cheezy poses, and sometimes asking other passnegers to take his picture for him.

As the sun set, we were passing an island half hidden by fog. The sun set behind it giving its rocky shillouette a colorful background (see the picture in a earlier post). We learned from a drunken Korean that it was a North Korean island, "a sad story". Perhaps it was North Korean. Perhaps that's why we were heading South at sunset and why the trip to Qingdao took 18 hours while the trip from Fukuoka took only six.

At night, we saw a horizon full of light. It looked almost like a far off city. The whole horizon glowed. It took hours to pass, and turned out to bebe a huge array of ships shining huge floodlights into the water. We assumed they were fishing for Squid.

In the morning, our first sight of China was a rocky island with a few trees on top and dozens of container ships on their way to stock the world's shelves with China's junk. Then, a thick fog surrounded usand from the deck, the water was barely visible. I didn't see anything until our ship was just off the coast of Qingdao. The fog was still thick and only the tops of skyscrapers were visible, floating in the grey morning fog.

Past customs and onto the street, on solid ground with a new group of friends, I traded some Won with a Korean named Song. The five of us tried unsuccessfully to flag a taxi until an older couple with a rickety van offered to take us to town for 30 Yuan. We wound up in a hotel with a fancy reception and small musty rooms with crickets in the sink on a dingy crunbling street in the center of downtown. China is poorer than I'd expected. Buildings everywhere are patched together, laundry is hanging everywhere people can manage to hang it, sometimes blocking the sidewalks, the sidewalks have missing stones, old people sit on rugs and plastic chairs along the streets, there are no stop lights, old crappy cars are all you see. We went into a large bank to change money, the roof and high walls inside had chipping paint and old water stains.

Past customs and onto the street, on solid ground with a new group of friends, I traded some Won with a Korean named Song. The five of us tried unsuccessfully to flag a taxi until an older couple with a rickety van offered to take us to town for 30 Yuan. We wound up in a hotel with a fancy reception and small musty rooms with crickets in the sink on a dingy crunbling street in the center of downtown. China is poorer than I'd expected. Buildings everywhere are patched together, laundry is hanging everywhere people can manage to hang it, sometimes blocking the sidewalks, the sidewalks have missing stones, old people sit on rugs and plastic chairs along the streets, there are no stop lights, old crappy cars are all you see. We went into a large bank to change money, the roof and high walls inside had chipping paint and old water stains.Qingdao is one of China's wealthiest cities in one of China's wealthiest provinces. An old German colony with disintegrating old German architecture adn good German beer. A sprawling old city with wide sidewalks and people selling things everywhere. The only place Aja can think to compare it to is, maybe, Cuba. It looks poorer than Chilie, she says. Perhaps this is what all cities will eventually look like.

We can't read menus and are doing our best to avoid water, undercooked meat, washed vegetables, and anything that could make us sick. No fresh food until we leave!

Gyeong-Ju

We spent our last three nights in Korea at a hostel run by a Mukashi-Nihonjin (old or ex- Japanese) in Gygongju. He had a small old voice, just like our Japanese teacher in Japan.

Gygongju was the ancient capital of the Silla empire, and today, it is a proud city. In its parks are huge burial mounds of Silla kings whose names have mostly been forgotten. The city is full of stinky fish markets and bustling streets with a seemingly unreasonable number of shops selling clothes. Just like in Japan, teh young people here wear silly English shirts that say things like "Return to Africa", "World Without Strangers", "Every Jack and Lucy Gill"....

Korea is hot. Scorching sun, high humidity, we drink lots of bottled water. There are more churches than temples, and they all look the same. At night they all have a big glowing red cross high in the sky. The downtown streets are lit with neon at night, but are surprisingly silent. The countryside here is more like Europe's than Japan's -- wide valleys with only glowing green rice fields, and no houses. In Japan, I never saw flat land that wasn't dotted with houses. Only plastic greenhouses and long plastic umbrellas covering the rows of vineyards reminded me of Japan. Some towns here consist almost entirely of highrise apartments. A few vertical neighborhoods and then countryside, fields and forest again. The Koreans seem to have the same love of building bridges over towns and fields as teh Japanese. Korean forests are less managed. Crooked, nobbly pines are most common--not the good straight lumber-forests of Japan.

Korea has visible problems. Poverty, beggars with damaged limbs who crawl through subway cars, who yell at people who don't give, who display their injuries, who wait in the sun for pocket change. They don't hide it in Korea. People fight, have arguements in the street. We saw an old man shove an old lady as she shouted at him and threw cardboard at him. Farmers sit on the sidewalk or on pieces of styrofoam and sell wilting vegetables and bruised fruit. They sell them for almost nothing. Perhaps Japan would be less shy and superficial if it were poorer. I wonder what it was like when it was poor, if I would recognize the culture the Japanese grandparents grew up in.

On the trains and subways, people will come on to sell things. On this train, a man walks through the train chanting like a monk and carrying bags of dried squid, and now he's changed to selling something else. On the subways in Pusan, one man sold a vegetable slicer and covered his face with thin slices of cucumber during his well-rehearsed skit. He even sold a few for $5 each. Another salesman, who didn't sell anything while we watched, sold mats that were foil on one side and tatami on the other. He folded them and unfolded them, giving reasons we didn't understand why we should buy them.

In Korea, there are only 250 last names.

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Our boat was huge. As big as a mall. It moved quickly with a steady, smooth rumbling. We shared a cabin with a group of other guys and had folded mattresses in stacks against the wall to unfold when we needed sleep.

Having misread our itinerary, I thought our six-hour trip would take at least 16, and was surprised to see land when I went out on deck to see if the deep sea really does smell different from coastal waters, as I had read in a book.

I spent my time on the boat talking to several Koreans, and got the impression that they are far more outgoing than the Japanese. One guy came up to me and wanted me to take his picture. I thought that was a strange request and he must have actually wanted me to take his picture, so I did. He actually hadn't misspoken, and wanted to take my picture, and for that, he brought me a beer and sat next to me and we talked for hours. He spoke English fluently and had been living in Japan the last several years.

Before we left the boat, we had several offers to stay at people's houses in Seoul and a slightly chunky guy with square half-rimmed glasses, who hadn't said much the whole way wanted us to follow him when we got off the boat. He told us he wanted to show us where to find cheap hotels, and we agreed to follow him.

Our ship was grand inside. Three stories of rooms, a spacious restaurant and open commons with cushioned chairs on each storey. There were rooms for Karaoke, beer vending machines, and a long deck where we could let the wind and mist blow through our hair and watch the sea go by. Through our binoculars, the horizon was speckled with small boats.

The ship was relaxing and pleasant. I found it much nicer than traveling by plane. We were not confined to a seat next to any particular person. The whole time, we could walk around, lie down to sleep, mingle, eat in the restaurant ... Customs was also much less invasive. No x-rays, rules about what you can have in your water bottle or extensive security procedures.

The ship moved so smoothly that I didn't even notice when it began to move, and could just see the golden dome of Fukuoka disappearing into the haze when I finally went outside to wait for the ship to depart. The ocean was a deep blue until we got to Pusan and it turned a coffee brown.

----------------

The hills around Pusan harbor just behind the docks and its huge red cranes are full of houses piled up on top of each other. Each one is a different color, has a flat roof, square windows, a blue container on the roof for water and almost no space between them. It looks almost like the Mediterranean, the colors are almost like Mexico. Our ship pulled deep into the bay with city and mountains on all three sides. Smaller boats went back and forth far beneath our deck and even larger boats sat like mountains blocking the coastline. It was a big, busy port full of containers and cranes.

With our backpacks on, we walked off the boat. Our new friend, Kwong, was telling us to follow him, we followed all the passengers into the quarantine to show our passports to Korean customs. We kept following Kwong, didn't have time to stop at Tourist Info and orient ourselves. We followed Kwong into the city, across a vast intersection with six lanes of impatient traffic. Across the street too big to have been in Japan, and down onto a neighborhood road too dirty to have been in Japan, with people standing around, talking, loitering, not as busy as people in Japan. This was definitely not Japan. We were hungry, our friend was asking around about where to eat.

Around a corner we brought our bikes up some nondescript, grey stairs into the entrance of a tall apartment building. "Lock your bikes", Kwong told us, asking if we thought they would be safe there, as if we knew better than he. Then, we went into an unmarked glass door with a red frame and found ourselves in a restaurant. A big menu hung on the wall, but we couldn't read anything but the prices.

Our food arrived sizzling loudly in thick, black stone bowls. Rice, spicy vegetables, Chile sauce and a dozen small plates of extras: Kimchi, Daikon, Chilies and other things I don't know the names of. The dish, we learned, is called Bibinbap. It's a good name, good food, and a spicy reminder that we had left Japan.

In Japan, everybody always pays for their own food. If you eat with a group, unless it is your principal taking you out on the mandatory end-of-semester lunches, restaurant tickets are always broken up. At my Conversation Night in Japan, I rounded up my tab by about ten yen and gave an even 500 to one of the ladies there. Two weeks later, she insisted that I take back my ten yen, saying that if you laugh at ten yen, ten yen will cause you problems later. I laughed and took it back.

In Korea, we were almost completely unable to pay for our own meals when we went out with other people. Kwong paid for our dinners and called his friend, Baek, who spoke excellent English and met us in the subway station. There, the team of two found us a room in the fanciest love hotel we've ever seen. It had internet, a wall-sized TV, a bath with full jacuzzi and a smaller TV built into the wall above it, a shower that doubled as a steam room, a huge bed, filtered water with a hot and cold tap and one of the fancy toilets I'd only seen in Japan with the console of buttons.

We thanked our new friends for their efforts, but that was not goodbye. Our itinerary for the evening also included drinks with the aspiring "dentalists". Our beer came in a 3 liter, mug-shaped pitcher and our table had sunken holes with cooling elements in them in which our personal beer caraffes fit and were kept icy.

Nightscape of Pusan from the window of our 18th story hostel window.

In the countryside, some towns are little more than a few highrise apartment buildings.

In the countryside, some towns are little more than a few highrise apartment buildings.

The last Korean Island we saw from the boat as the sun set.

Aja and I at the enterance to one of the tombs in Gyeong-Ju.

Our first sight of Korea in Pusan Harbor. View of Pusan's superhighways and mega- apartments